Returning now back to those things engineering, the question for today is, “Is there ever a time when incomplete information, on a drawing for instance, communicates the design intent better than a fully completed and dimensioned drawing?” Surprisingly, the short answer is, “yes.” Now, I am sure that many will emphatically point out that omitting data can never be the way to go in defining a part and they are correct. So how can both statements and conditions be true and under what circumstances can they coexist? Let’s look at an example to show the concept and the solution.

An example that comes to mind comes from the packaging industry. Let’s look at a typical clear plastic “blister” that is used to show a product while protecting it from damage in both shipping and handling. It will usually be either heat-sealed to a backing card of some type or just stapled to it. First we need to look at how the blister is made. The process is called vacuum-forming, by which a sheet of clear plastic is heated up to its softening point and then drawn down, using a vacuum, to form it around a mandrel which gives it its shape.

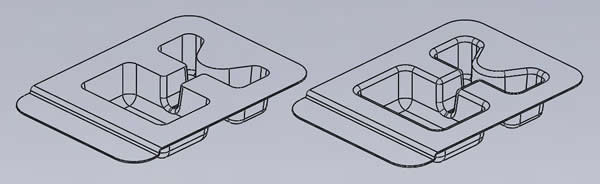

As in most processes, there are some types of features you can get “free” and others that are very costly to produce. You might remember that machining a part gives you vertical walls while an injection molded part provides parts with draft – in both cases, for “free.” However, making injection molded parts with no draft, while putting “draft” on machined parts is considerably more costly – but it can be done! Now what are the specific “free” and “costly” features of the vacuum-forming process? The vacuum-forming process “likes” large draft angles, large fillet radii and lots of room between vertical (or near-vertical) walls. By the same token, it does not “like” vertical walls with little or no draft, sharp corners at the bottom of pockets (or anywhere for that matter) and vertical walls that are spaced closely together. When you fully grasp to concept that the plastic sheet is being stretched while being formed, these “likes” and “dislikes” become very apparent. With all of these generous draft angles and fillets all over the part, how then do you communicate, with precision, your design intent? Look at the following two sketches for the blister for a Wishbone Drill.

In the left drawing, the fillets on the top plane have been omitted. It is now very easy to place accurate dimensions on this drawing, with the various features (pockets) now clearly defined. However, the actual part is as shown in the drawing on the right. So, the answer is to provide the client with both drawings, the one on the left to be used mostly for laying out the job and for checking while the one on the right can be used for rapid prototyping or for CNC machining of the actual mold.

Keep in mind that what you are doing is just being a guide for the tooling and production of the part. So, whatever communicates the concept most clearly is the way you want to go.

Please call me if you’re having any design or manufacturing issues. I’ll help you sort it out.